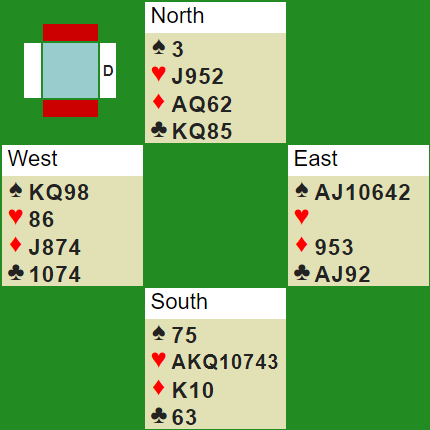

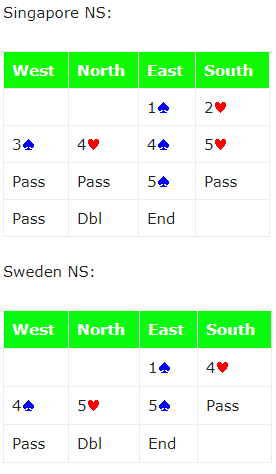

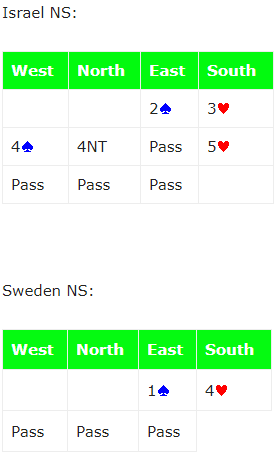

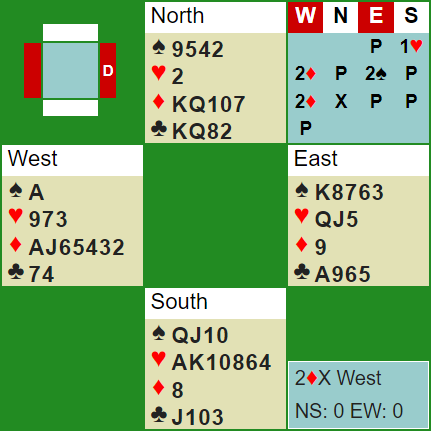

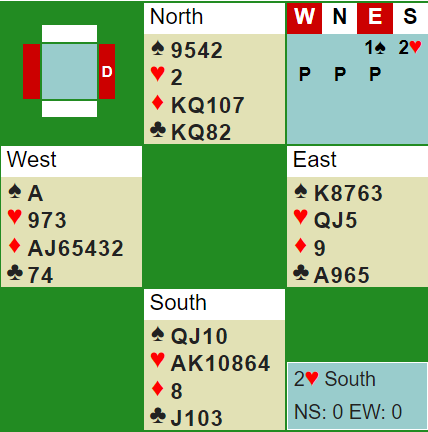

AuthorThe late Gabino Cintra, a World Pairs champion (playing with Marcelo Branco) from Brazil, liked to wax poetical about the everlasting battle between spades and hearts. He was a frequent vugraph commentator from Brazilian and South American events, and he would have enjoyed the following board greatly. Board 2 from the World Youth Teams Championships finals was yet another skirmish between the two ancient opponents. Let’s take a tour through the tables where these cards were on display and see if there is something to be learned from the auctions.Examining the four hands in the quiet environment of our screens, we can see that NS will make 11 tricks in hearts; and that EW have a profitable sacrifice in 5S, paying only 300 in doubled undertricks. But things are never as clear as that when you are looking at only ¼ of the deck, in an important match. U-26 Open (Singapore vs. Sweden):

4 Spades by West was much less well defined (ranging from a good hand with 3-card support to a bad hand with lots of trumps). Yu Chen Liu, as East, had a difficult decision when he bid 5 Spades at this table; partner could have had a very unsuitable hand (with more stuff in the red suits). He took the opponent’s red vs. white bidding at face value and everything turned out for the best. North had a clear double at both tables. U-26 Women (China vs. Poland):

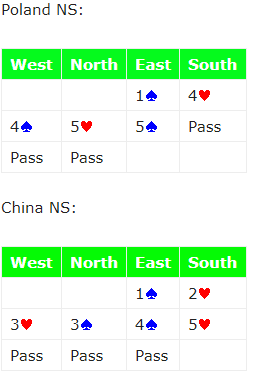

U-21 Open (Israel vs. Sweden):

0 Comments

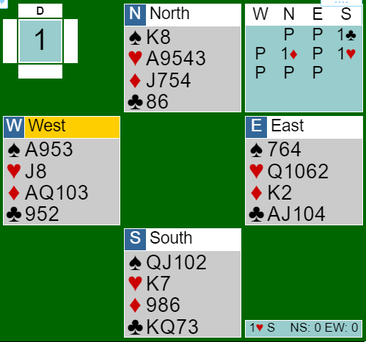

AuthorBoard 6, from the 3rd segment of the 2018 Junior final between Sweden and Singapore, was very difficult to navigate properly. The traps were dangerous, and they were everywhere. East was the dealer, and EW were vulnerable against not. Let’s look at it from West’s viewpoint: A nice looking hand. When Adam Stokka from Sweden held this hand, his partner passed and RHO opened 1 Heart. What would you do? Most people would probably bid a simple 2 Diamonds, but I think a case can be made (facing a passed partner, and vul vs. non-vul) for the 3 Diamonds overcall. Would it have made any difference? Perhaps, for this was the full hand: After the first bid by West, the bids were all pretty much forced. I would not say that East could never pass 2 Diamonds with that hand, but I can say that I would never do it. And the final result was 500 for Singapore, when EW lost the obvious 6 tricks (2 hearts, 3 diamonds, 1 club), due to the spade blockage which prevented the King of spades from adding any trick to declarer’s total. After an initial 3 Diamonds overcall, North would not have a natural penalty double. Would South reopen? He should, but there is no doubt that it is easier for North to double 3 Diamonds than for South to do it. Meanwhile, in the other room, the Singaporean pair nimbly avoided any trouble in the bidding with these cards: There are lots of little things going on in hands like this that explain the big swing. In this auction, the first component is East’s light opening (in a Precision context), even vul vs. non-vul. Many people refrain from light openings because they are, allegedly, risky. But any coin has two sides: sometimes a light opening helps you avoid trouble.

This is not enough to explain EW’s escape, though: full marks must also be given to Jazlene Ong’s restraint with the West cards (and again, the light opening context of Precision helped a lot there). The “death holding” of xxx in the opponent’s suit, the blocking SA, the weak (even if very long) suit, were all warning signs that were duly noted. (I speak here as someone who would have a great deal of difficulty in finding this pass). Curiously, though, the bidding success was followed by a trick lost in defense, enabling N-S to go plus in their 2H contract. The Ace of Spades was led, and West then shifted to a club; King of spades (club pitch), spade ruff, dA, and now, when West played a diamond, East did not really believe that his partner had passed with a 7-card suit headed by the AJ and a side Ace, and so ruffed small! Ida Grönkvist gratefully overruffed cheaply, drew trumps, and made 8 tricks. But Singapore accepted the 9 IMPs (rather than the 11 they might have gotten if East had ruffed high). AuthorSweden had a superb performance in the 2018 World Youth Teams Championships, winning the Under-26 and Under-21 categories. In the U-26 (also known as the Juniors), the finals were played against Singapore, a country which has been steadily placing higher at World Championships in the past years. Those who follow Junior bridge know that, at the highest levels, the game is extremely aggressive and well played, and that the partnerships employ very sophisticated methods with great competence. When the finals of the 2018 World Championship began, the first board was an example of all that. These were the cards – being Board 1, this was all white, and North was the dealer: It is not unimaginable that a board like this would be passed out in many games, but that would not happen in present company. When the Swedes held the North-South cards, they were able to stop low by means of a transfer response, as seen in the diagram. 1 Diamond showed 4+ hearts, and 1 Heart showed a weak balanced hand. North was pleased to stop in 1 Heart.

Should EW have tried harder to push the Swedes around? Then again, they can’t even make 1NT, so that is not without its risks. In any case, N-S cannot make 7 tricks, right? They are slated to lose 1 spade, 2 hearts, 3 diamonds and 1 club. But this is without taking into account the advantage of transferring the play of the hand to South. West started with a difficult lead, and picked the 5 of spades. Ida Grönkvist played the King from dummy, as East discouraged with the 7. Declarer played a second spade. East did his best to encourage a diamond switch by playing the 6 of spades in that trick, but it was not enough; West played a third spade, and declarer seized the opportunity to discard two diamonds from the table, as East ruffed with a natural trump trick. That was that. Perhaps West should heed the old saying that both sides should not be attacking the same suit, but we must credit the transfer response with some part of this result. This was already a good result for Sweden, but it became even better when Zhou for Singapore, at the other table, decided to open the North cards with an anemic 2 Hearts. This could have worked out better, of course, as is often the case with preempts, but I suspect that this decision was not purely technical; at the start of a very long match, it is tactically wise to plant some doubts upon your opponents’ minds regarding your style of preempts. In any case, if it worked out fine, it would give the Singaporeans a psychological edge. As it happened, though, it backfired when West reopened with a double and East decided to pass rather than to look for a game. (This decision, facing an unpassed partner, was also probably influenced by psychological and tactical considerations – grabbing a penalty at the first board is never unwelcome). The sum of both decisions was a great board for Sweden, compounded by the fact that when dummy was South, West had little difficulty in switching to a small diamond after winning the Ace of spades. (A spade was also led here, by East). The Swedes defended carefully to extract the maximum penalty: spade lead ducked, then West won the continuation and played a small diamond; East won the King, cashed the Ace of clubs, and returned a diamond. As West cashed his diamonds, East pitched the last spade. A spade was played for a ruff, and a further trump trick was lost later. 300 and 80 for Sweden amounted to a good start, 9 IMPs. |

Archives

September 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed